A is almost 13 months, so walk into our house almost any day and it’s likely you’ll see some sort of minor temper tantrum within twenty minutes. It normally only lasts 10-30 seconds, but it can be a theatrical treat: back-arching, nose-crinkling, fake crying. And this can happen in response to almost anything. Today, I didn’t let him chew on the bottom of my gross flip flop. How dare I!

As easy as it is to [half-] jokingly complain about these moments, I consider them opportunities to cultivate a critical social justice skill in my son: empathy. My in-laws lovingly make fun of one phrase that I’ve seemed to say to A every time he starts to fuss:

Are you feeling frustrated?

The response is an attempt to recognize and name the emotion that A is feeling in those moments. To manage a temper tantrum by acknowledging what he is feeling, first and foremost. To legitimate his emotions. I’m sure he really is frustrated that he can’t chew on my shoe, no matter how ridiculous that seems to us.

The way we talk to kids about their emotions—particularly our sons—is a one of those mundane, critical acts of social justice. Too often, boys are subtly (or not so subtly) taught to mute their emotions. Speaking to A about his emotions cultivates his emotional intelligence and ultimately models compassion for him. By saying You seem really sad right now!, I want to encourage him to recognize and honor emotions in himself and (later) in others. Particularly in the cultural context of toxic masculinity, I try to be cognizant of using “emotional vocabulary” with A—and to teach him not to be ashamed of expressing or recognizing his emotions.

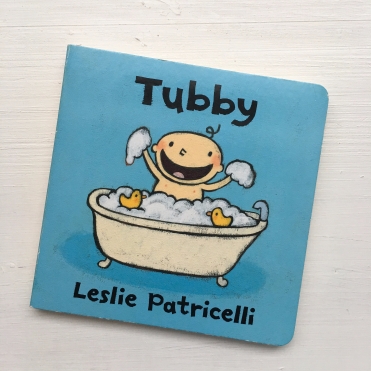

I’ve recently started pointing out illustrations in books of characters showing a lot of emotion. It’s a similar idea: that small, mundane act encourages him to recognize emotions in others and build empathy for them.

Empathy is a necessary–though not sufficient–step in becoming a human being who cares about social justice. It teaches us to care about others’ emotional states, even if they don’t match our own. Empathetic people can still be racist, sexist, etc., of course. Blame human social psychology and all that in-group/out-group BS for that. BUT an anti-racist/sexist/oppression person inherently must be empathetic. It is a prerequisite, but not the only one.

*P.S. I don’t think this is a revolutionary approach by any means–lots of parents have being doing this for years. Still, I do think it is still helpful to consciously and explicitly state what might be an unconscious thought or practice.